OSTEOMYELITIS

- Suppurative osteomyelitis

- Garrés osteomyelitis (periostitis ossificans, proliferative osteomyelitis)

- Tuberculous osteomyelitis

- Syphilitic osteomyelitis

- Actinomycotic osteomyelitis

- Osteoradionecrosis

SUPPURATIVE OSTEOMYELITIS

Osteomyelitis is an inflammatory reaction of bone to

infection which originates from either a tooth, fracture site, soft tissue

wound or surgery site. The dental infection may be from a root canal, a

periodontal ligament or an extraction site. Suppurative osteomyelitis can involve

all three components of bone: periosteum, cortex, and marrow. Usually there is

an underlying predisposing factor like malnutrition, alcoholism, diabetes,

leukemia or anemia.

Other predisposing factors are those that are characterized

by the formation of avascular bone for example, therapeutically irradiated

bone, osteopetrosis, Paget's disease, and florid osseous dysplasia.

Osteomyelitis is more commonly observed in the mandible because of its poor

blood supply as compared to the maxilla, and also because the dense mandibular

cortical bone is more prone to damage and, therefore, to infection at the time

of tooth extraction.

Acute osteomyelitis is similar to an acute primary abscess

in that the onset and course may be so rapid that bone resorption does not

occur and, thus, a radiolucency may not be present on a radiograph. Clinical

features include pain, pyrexia, painful lymphadenopathy, leukocytosis, and

other signs and symptoms of acute infection. Later, after approximately two

weeks, as the lesion progresses into the chronic stage, enough bone resorption

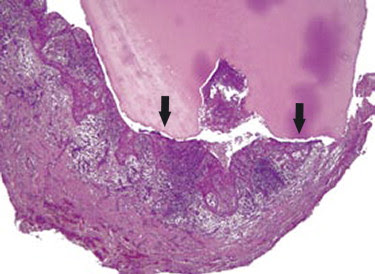

takes place to show radiographic mottling and blurring of bone. A sclerosed

border called an involucrum forms around the affected area. The involucrum

prevents blood supply from reaching the affected part. This results in the

formation of pieces of sequestra or necrotic bone surrounded by pus. A

fistulous tract may develop by the suppuration perforating the cortical bone

and periosteum. The fistulous tract discharges pus onto the overlying skin or mucosa.

The radiopacity of the sequestra and the radiolucency of the

pus give rise to the characteristic "worm-eaten" radiographic

appearance. Radiographs also aid in locating the original site of infection

such as an infected tooth, a fracture, or infected sinus.

Fig. 13-1 Chronic suppurative osteomyelitis of dental

origin. The lesion discharged pus into the oral cavity. Note the radiopaque

sequestra (arrow) surrounded by the radiolucent suppuration.

Fig. 13-2 Chronic suppurative osteomyelitis demonstrating a

worm-eaten appearance of the body of the mandible. Note the radiopaque

sequestra surrounded by the radiolucent suppuration and a radiopaque

involucrum. The patient had fetid breath.

Fig. 13-3 Chronic suppurative osteomyelitis of dental

origin. The radiopaque sequestrum (arrow) is surrounded by the radiolucent

suppuration.

Fig. 13-4 Sequestrum that has floated into the soft tissues.

Patient gave a history of a problematic tooth extraction several years ago

which resulted in clinical complications.

GARRÉS OSTEOMYELITIS

(Periostitis ossificans, Osteomyelitis with proliferative periostitis)

Garrés osteomyelitis or proliferative periostitis is a type of chronic

osteomyelitis which is nonsuppurative. It occurs almost exclusively in children

and young adults who present symptoms related to a carious tooth. The process

arises secondary to a low-grade chronic infection, usually from the apex of a

carious mandibular first molar. The infection spreads towards the surface of

the bone, resulting in inflammation of the periosteum and deposition of new

bone underneath the periosteum. This peripheral formation of reactive bone

results in localized periosteal thickening. The inferior border of the mandible

below the carious first molar is the most frequent site for the hard nontender

expansion of cortical bone. On an occlusal view radiograph, the deposition of

new bone produces an "onion-skin" appearance.

Fig. 13-5 Garrés osteomyelitis (proliferative periostitis)

demonstrating an expansion of the inferior border of the mandible (onion-skin

appearance) caused by the periapical infection of the mandibular first molar.

Fig. 13-6 An occlusal radiograph of Garrés osteomyelitis

showing the buccal expansion of the mandible caused by infection around the root

tip of the extracted first molar.

Fig. 13-7 Garrés osteomyelitis (periostitis ossificans)

exhibiting localized periosteal thickening. The source of infection is not known;

it could have been from an exfoliated deciduous molar tooth.

TUBERCULOSIS OSTEOMYELITIS

Tuberculosis is a chronic granulomatous disease which may

affect any organ, although in man the lung is the major seat of the disease and

is the usual portal through which infection reaches other organs. The

microorganisms may spread by either the bloodstream or the lymphatics. Oral

manifestations of tuberculosis are extremely rare and are usually secondary to

primary lesions in other parts of the body. Infection of the socket after tooth

extraction can also be the mode of entry into the bone by Mycobacterium

tuberculosis.

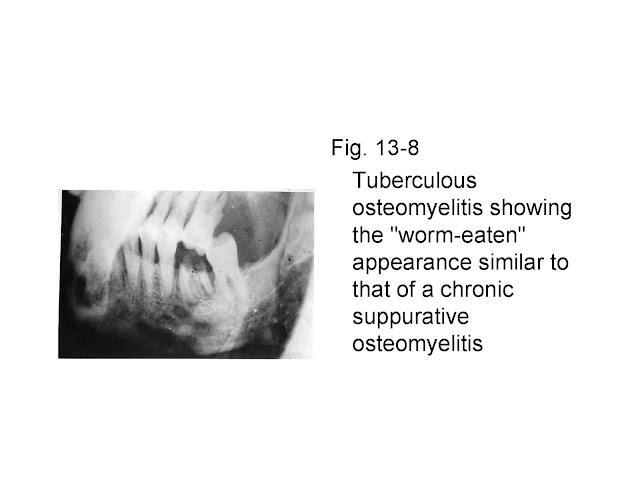

Mandible and maxilla are less commonly affected than long

bones and vertebrae. On a radiograph, the appearance of bony lesions is similar

to that of chronic suppurative osteomyelitis ("worm- eaten"

appearance) with fistulae formation through which small sequestra are exuded.

Periostitis ossificans (proliferative periostitis) can also occur and change

the contour of bone. Calcification of lymph nodes is a characteristic sign of tuberculosis.

Fig. 13-8 Tuberculous osteomyelitis showing the "worm-eaten"

appearance similar to that of a chronic suppurative osteomyelitis

Fig. 13-9 Calcified tuberculous lymph nodes

SYPHILITIC OSTEOMYELITIS

Syphilis is a chronic granulomatous disease which is caused

by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. It is a contagious venereal disease which

leads to many structural and cutaneous lesions. Acquired syphilis is

transmitted by direct contact whereas congenital syphilis is transmitted in

utero. In congenital syphilis, the teeth are hypoplastic, that is, the

maxillary incisors have screwdriver-shaped crowns with notched incisal edges

(Hutchinson's teeth) and the molars have irregular mass of globules instead of

well-formed cusps ("mulberry molars"). Also, a depressed nasal bridge

or saddleback nose occurs because of gummatous destruction of the nasal bones.

Acquired syphilis, if untreated, has three distinct stages.

The primary stage develops after a couple of weeks of exposure and consists of

chancres on the lips, tongue, palate, oral mucosa, penis, vagina, cervix or anus.

These chancres are contagious on direct contact with them. The secondary stage

begins 5 to 10 weeks after the occurrence of chancres and consists of diffuse

eruptions on skin and mucous membrane. This rash may be accompanied by swollen

lymph nodes throughout the body, a sore throat, weight loss, malaise, headache

and loss of hair. The secondary stage can also damage the eyes, liver, kidneys

and other organs. The tertiary-stage lesions may not appear for several years

to decades after the onset of the disease. In this stage of osteomyelitis, the

bone, skin, mucous membrane, and liver show gummatous destruction which is a

soft, gummy tumor that resembles granulation tissue. Paralysis and dementia can

also occur. In the oral cavity, the hard palate is frequently involved

resulting in its perforation. The gummatous destruction is painless. Syphilitic

osteomyelitis of the jaws is difficult to distinguish from chronic suppurative

osteomyelitis since their radiographic appearances are similar.

Fig.13-10 Syphilitic osteomyelitis of the palate. The

gummatous destruction has produced a palatal perforation.

Fig.13-11 Radiograph of syphilitic osteomyelitis of the

palate. The perforation which is the site of gumma of the hard palate produces

a radiolucency which may be mistaken for a median palatine cyst.

ACTINOMYCOTIC OSTEOMYELITIS

Like tuberculosis and syphilis, actinomycosis is a chronic

granulomatous disease. It can occur anywhere in the body, but two-thirds of all

cases occur in the cervicofacial region. The disease is caused by bacteria-like

fungus called Actinomyces israeli. These microorganisms occur as normal flora

of the oral cavity, and appear to become pathogenic only after entrance through

previously seated defects. The portal of entry for the microorganisms is either

through the socket of an extracted tooth, a traumatized mucous membrane, a

periodontal pocket, the pulp of a carious tooth or a fracture. In cervicofacial

actinomycosis, the patient exhibits swelling, pain, fever and trismus. The lesion

may remain localized in the soft tissues or invade the jaw bones. If the lesion

progresses slowly, little suppuration takes place; however, if it breaks down,

abscesses are formed that discharge pus containing yellow granules ( (nicknamed

sulfur granules) through multiple sinuses.

There is no characteristic radiographic appearance. In some

cases the lesion resembles a periapical radiolucent lesion. The more aggressive

lesion resembles chronic suppurative osteomyelitis. In chronic suppurative

osteomyelitis there is usually a single sinus through which pus exudes;

however, in actinomycotic osteomyelitis there are many sinuses through which

pus and "sulfur granules" exude.

Fig.13-12 Actinomycotic lesion similar to radicular cyst.

This is not a typical appearance.

OSTEORADIONECROSIS (and

effects of irradiation on developing teeth)

In therapeutic radiation for carcinomas of the head and

neck, the jaws are subjected to high exposure doses of ionizing radiation

(average of 5000 R). This results in decreased vascularity of bone and makes

them susceptible to infection and traumatic injury. Infection may occur in

irradiated bone from poor oral hygiene, extraction wound, periodontitis, denture

sores, pulpal infection or dental treatment. It is therefore advisable that a

patient scheduled to undergo therapeutic radiation be given dental treatment

prior to radiation therapy and that after radiation therapy the patient be

taught to maintain good oral hygiene.

When infection occurs in irradiated bone, it results in a

condition called osteoradionecrosis which is similar to chronic suppurative

osteomyelitis. The mandible is affected more commonly than the more vascular

maxilla. Therapeutic radiation may affect the salivary glands, producing

decreased salivation. The resulting temporary or permanent xerostomia is

responsible for radiation caries of teeth and erythema of the mucosa.

A radiograph of osteoradionecrosis, shows radiopaque

sequestra and surrounding radiolucent purulency similar to that of chronic

suppurative osteomyelitis. The two cannot be differentiated radiographically

except by the history of therapeutic radiation. Effects of irradiation on

developing teeth depends on the stage of development when irradiation occurs

and on the dosage administered. The injured tooth germs may either fail to form

teeth (anodontia), exhibit dwarf-teeth, produce agenesis of roots, shortening

and tapering of roots, or develop into hypoplastic teeth. The eruption of teeth

may be retarded and their sequencing may be disturbed. Other radiation induced

effect may include maxillary and/or mandibular hypoplasia.

Fig.13-13 Occlusal projection of anterior region of mandible

showing osteoradionecrosis. Notice the destruction of the trabecular pattern of

bone.

Fig.13-16 Dwarfing of teeth as a consequence of radiation

therapy